Breathing Emily

- 112 minutes read - 23655 wordsINTRODUCTION

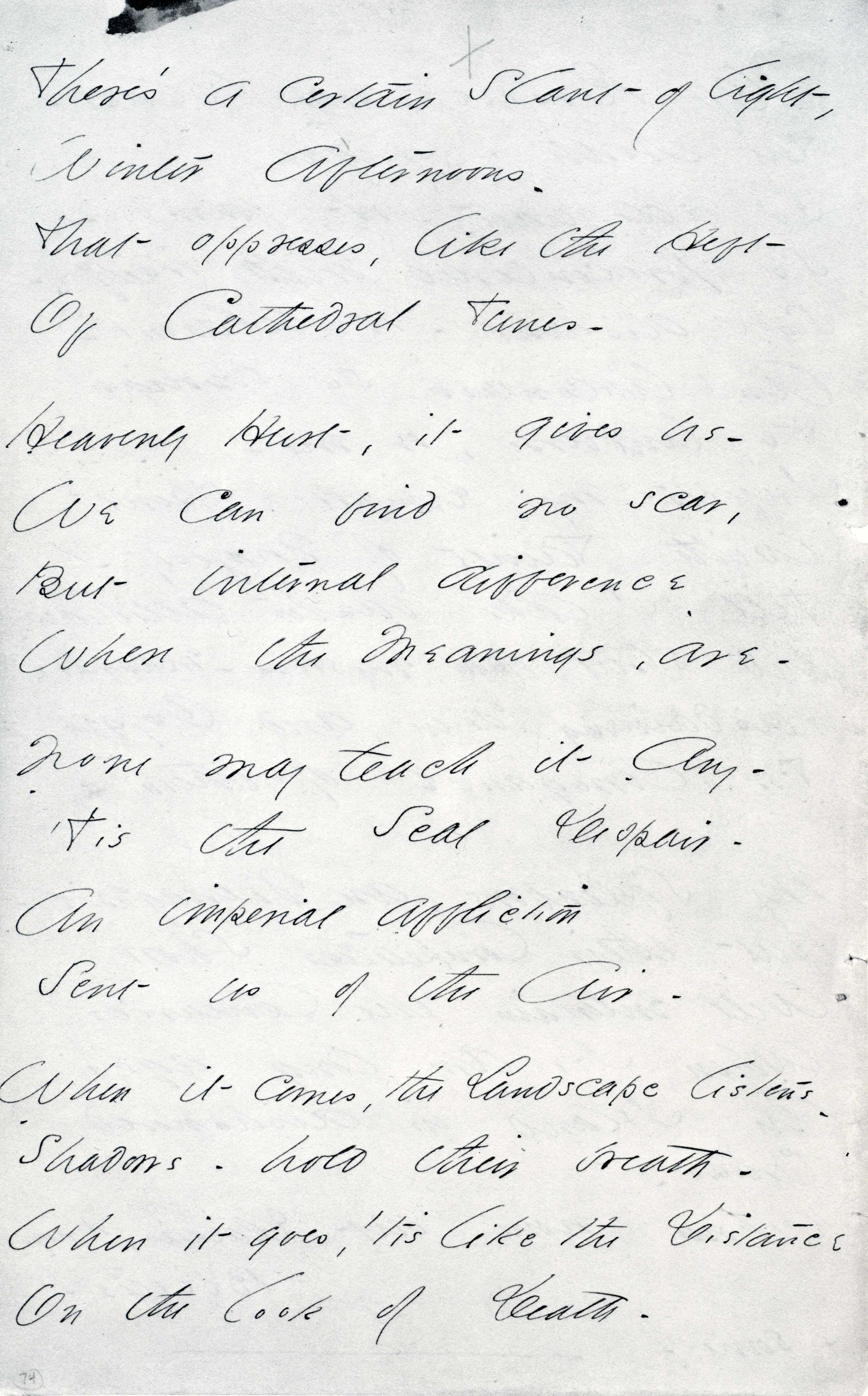

The poetry of Emily Dickinson is characterized by her willingness to challenge convention, most characteristically through her use of “dashes” in addition to normal marks of punctuation. Now that the digital representations of the actual manuscripts of her poetry are widely available, we are becoming even more fully aware of the nuanced appearances of the texts. The goal of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of the dashes found in the poetry of Dickinson by exploring the subject matter of her poetry, manuscript material, and biographical events in her lifetime in light of my own research and new developments in Dickinson scholarship.

I am extending previous speculations about the punctuation into one further aspect of inquiry. I have been investigating the correlation of the dash patterns to a medical phenomenon known as “mouth breathing.” In her correspondence with Atlantic Monthly Editor T. W. Higginson, Dickinson emphasizes that Higginson has described the “gait” of her poetry as “spasmodic,” referring to its pace (Letters 409).1

I hope my efforts to relate the origin of the dashes in her poetry to her own literal breathing patterns will result in a further understanding of the appearance of the dashes in her poetry, and of the relation of the dashes to the overall recurrent figure of breathing itself in her poems and letters. Without necessarily proving my point definitively, I want to explore biographical and textual considerations that cause me to believe that Emily Dickinson was likely a mouth breather, and that her mouth breathing is a plausible explanation for her use of dashes. In other words, I think it very likely that Emily Dickinson might have been a mouth breather, and that this one physiological irregularity could explain her highly unconventional—even unique—punctuation.

Emily Dickinson was born into the world of breathing in 1830. Yet ever since her poetry was first shared with a select few, it has been literally gasping for breath. For a period of time, when her poetry was found and first published, it was nearly smothered. The original editors of Dickinson found it necessary to regularize her unique use of punctuation, primarily by suppressing the dashes, and to standardize such other things as capitalization and diction. Little did they know, they were actually extinguishing much of the very life of Emily Dickinson and her poetry.

As the second half of the twentieth-century emerged, Dickinson’s poetry began to breathe more freely. Scholars and enthusiasts alike experienced the poetry of Emily Dickinson along with her breath—in the form of the rhythm that punctuation definitively helps supply in poetry—for the very first time. The punctuation returned to her poetry when it was published in full for the first time in 1955 by Thomas Johnson in The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. The new versions of the poems caused confusion, though, and even bewilderment in many cases. No one knew what to make of the abundant and elaborate use of dashes, the very breath of Emily Dickinson penetrating for the first time through the pages of her manuscripts, and scholars continue to puzzle over their significance.

In 1998, Ralph W. Franklin published The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition, improving still further upon the dating and representation of Emily Dickinson’s poems in the Johnson edition. This new edition of Dickinson’s poems includes all of the different known variants of each text, pulling together 1789 poems from in excess of 2500 scraps of Dickinson autograph manuscripts. Franklin’s representations of Emily Dickinson’s poems include her unique punctuation and capitalization, original spelling, variant word choices that she considered, and even notes on the manuscripts upon which the poems were found. This edition is and should continue to be considered the most accurate print representation of the poetry of Emily Dickinson.

Dickinson’s poetry is very dense and extremely complex, so most readers tend to see the dashes more as something to bypass rather than to understand. The brevity of her poems not withstanding, because of their difficulty there is plenty to work with in each poem, even when one dismisses the characteristic dashes. Yet scholars have long emphasized their importance. The Johnson and then the Franklin editions generated great progress in both the interpretation of her unusual punctuation and the understanding of the poems themselves. And, yet, something is still missing.

Scholars now lean toward examining the autograph manuscripts of Emily Dickinson, instead of traditional print representations of her poetry. Even Franklin’s edition has been pushed aside in order for scholars to focus on the series of marks Dickinson scratched across the small pieces of paper she wrote upon. Ironically, the first time most scholars and readers experienced the autograph manuscripts of Dickinson was in The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson, published by Franklin nearly two decades earlier than his variorum edition, in 1981. It now seems that every mark of Dickinson’s pen, or pencil depending on the period of time in her life, is seen as both purposeful and significant. Unfortunately, this trend only serves further to confuse the matter of Emily Dickinson’s dashes, which still remains unresolved today.

My study focuses extended attention on the origin and purpose of the dashes found so profusely in the poetry of Emily Dickinson. Until this matter is resolved, the poetry of Emily Dickinson will not truly be able to live and breathe. This is where the physical phenomenon of mouth breathing comes into play. My thesis makes the biographical speculation that Dickinson’s dashes could have stemmed from her being affected by the medical condition known as “mouth breathing.” Mouth breathing is an inherently simple explanation for the origin and use of dashes in Emily Dickinson’s poetry and, as this thesis will explore, fills in many gaps left in the understanding of both the life of Dickinson and her writing.

Mouth Breathing

Life both begins and ends with a single breath. In between these two breaths, breathing—a natural reflex that unconsciously replenishes the body with oxygen—is often ignored. However, breathing is the most fundamental action taken by creatures in order to live on Earth. People die because their bodies are unable to supply their cells with oxygen, because their bodies are unable to breathe. A lack of any other form of sustenance cannot kill a being faster than the lack of air. The act of breathing is so necessarily fundamental that our bodies cannot even afford to rely on us to gather air consciously—it is something that must be done automatically and continuously. Air is generally provided by the action of breathing, and we typically breathe through the nose. The act of breathing has been so refined through the development of the human being that simply breathing through the mouth instead of the nose has immense and dire consequences on the health of the entire human body.

Everyone can breathe through her mouth. In fact, everyone does at some point during her life. Whenever exercise occurs, for example, a human being often breathes simultaneously through both her nose and mouth. However, breathing solely through the mouth, instead of the nose, has adverse effects on the health of a human being. Mouth breathers generally begin breathing through their mouths because they have no other choice. The nose is blocked entirely, by nasal polyps or because of allergies for instance, to such an extent that breathing through it becomes impossible to sustain life. The body naturally compensates for the lack of nasal breathing by the taking in of air through the mouth and into the lungs.

The Western medical and scientific understanding of the effects of mouth breathing began to take shape over a hundred years ago, toward the beginning of the twentieth century. Even then, the effects of mouth breathing appear to have been often overlooked by physicians. As Dr. Joe O. Roe notes in The American Journal of Nursing as early as 1903, “There is no perverted function attended with so many ill effects, and none persisted in so continuously and with as little concern, as that of mouth-breathing” (87). Continuing with the introduction to his essay “Mouth-breathing—Its Injurious Effects,” Dr. Roe even takes the time to emphasize how long the observation of nose-breathing as healthy has been present throughout human society: “In proof that man was intended to be a nose-breather we might cite the authority of divine writ, when it says, ‘The Lord breathed into his nostrils the breath of life,’ which shows that the ancient Jews had a proper conception of the nose as a divinely appointed organ of breathing” (87). The seemingly benign effect of changing the path by which air flows through the head, even over a hundred years ago, was understood and characterized as drastic.

Perhaps the primary danger of mouth breathing is increased risk of infection. While the sense of smell is associated with the nose, smell is not the primary function of this organ. The removal of dust, foreign objects, and germs by the nose is thwarted by the act of mouth breathing. Mouth breathing thus makes people more prone to breathing in viruses and germs, because the body’s primary defense for such invasions is bypassed. As Roe emphasizes, “the nose in filtering the air . . . is consequently of the greatest importance in the prevention of pulmonary disease” (88). Even more, as I will discuss in chapter one, it is quite significant that Roe connects consumption directly to mouth breathing: “Mouth-breathing, therefore, may be regarded as one of the principal predisposing causes of consumption, while nose-breathing is the natural safeguard for its prevention” (89).

Adding to the problems of mouth breathing, the nose also humidifies the air breathed into the lungs through normal nasal breathing. This process is so vital that nerves in the nose regulate the moisture in the nasal cavity in order to meet the needs of various qualities of air breathed in. Air bypassing the nasal cavity via mouth breathing is not humidified to the appropriate level for adequate consumption by the lungs. The throat and lungs thus often become irritated because of dry air inhaled though the mouth. Even the temperature of the air breathed into the lungs is modified by the nasal cavity, preparing it for use by the lungs. Roe writes: “As a result of mouth-breathing the throat becomes dry and irritable, the larynx irritated, attended with hoarseness and cough; the person is made more susceptible to colds” (89).

Mouth breathing even has drastic visible effects on the physical development of a human being. The lack of proper air impairs the growth of the chest of a child who breathes through her mouth, and the chest becomes “abnormally contracted” (90). The nose is itself also drastically affected by the lack of airflow, remaining “small and contracted,” and “the end of the nose frequently becomes abnormally enlarged” (90). Both of these descriptions are consistent with the physical attributes of Emily Dickinson’s torso and nose found in the two extant pictures and one silhouette image of her that survive today. The connection between the physical effects of mouth breathing and the images of Emily Dickinson cannot be denied, and serve to further the evidence in her life and writing that accent her mouth breathing as well.

Finally, the sense of smell is thwarted by one’s breathing through the mouth instead of the nose. Roe, like many doctors who investigate mouth breathing, believes that breathing’s bypassing the nose suppresses the sense of smell. More modern studies have conclusively found the sense of smell lacking in oral breathing, something that is believed to be necessary for living a fulfilling life. Smelling, of course, is a large part of the sense of taste as well.

Breathing has become increasingly important in modern health practices. More modern interpretations of breathing associate the lungs themselves with energy levels. In the Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, Dr. Sivansankar explains that breathing through the nose causes back pressure in the lungs, allowing for the constant absorption of oxygen by the bloodstream. Mouth breathing does not generate back pressure in the lungs, which alters the pH balance of the bloodstream. The effect on the mouth breather is an increase in vocal effort necessary to sustain proper speech (1416-18). Properly breathing through the nose regulates the body and pulse, reducing hypertension and stress. The more that is learned about mouth breathing, the more it is realized that it has an undeniable effect on the entire health of a human being.

Dickinson’s Poetry and Breath

The most unique feature of Emily Dickinson’s poetry is her dashes. One primary effect of the dashes involves rhythm. Dashes represent longer syntactic pauses than do commas, and therefore they provide Dickinson’s poems with a very erratic and entirely singular rhythm. Thus Dickinson’s poetry is in part characterized by her unusual representation of the pace of language. One of my main points is that the “spasmodic” pace of Dickinson’s poetry is consistent with the seemingly irregular rhythm of the speech patterns of mouth breathers.

As I will explore more fully in chapter two, research on the dashes alone provides major points in a number of articles and books and is the primary focus of one book on Dickinson. Those who claim to have found the origin of the dashes are immediately challenged by skeptical scholars and, to date, their mystery has never been adequately explained. The matter is further complicated by the fact that Dickinson left behind a vast correspondence with many different individuals, and those letters are quite similar to the poems themselves. In fact, the scholar who is most experienced with Emily Dickinson’s manuscripts, R. W. Franklin, informed Dickinson scholars: “any special theory about Emily Dickinson’s manuscripts will have to fit both poems and letters” (120). The characteristics of Emily Dickinson’s poems are inherent in all of her writing.

The first chapter of this thesis addresses the issue of Dickinson herself. The life of Emily Dickinson is exceptionally complex, especially for an individual who spent a good portion of her life inside her father’s house. I will connect the phenomenon of mouth breathing to Emily Dickinson through the history of her life that is available. Through her writing, primarily the correspondences she had with others, I will explore how Emily Dickinson wrote to others about her various illnesses and how those correspondences relate to my argument of her possibly being a mouth breather. In addition, the perspectives of other individuals about Emily Dickinson and their recorded interactions with her will reinforce this thesis. The voice and breath of Emily Dickinson are often commented on by those who knew her, in ways that reinforce a representation of her as a mouth breather.

The second chapter focuses on the formal attributes of the dashes in Dickinson’s poetry. I represent graphs of the occurrence of the dashes in ways that visually further our understanding of the punctuation. I then use that data to engage with previous arguments about the dashes and to dispel some of the conclusions that scholars have drawn. I also make connections between the trends and frequencies of the appearance of the dashes to the theory of Emily Dickinson’s being a mouth breather. Finally, I analyze selections of her handwritten manuscripts for similar purposes.

The final chapter deals with breath and respiratory illness as topics and tropes in Dickinson’s writing. Respiration is a very important concept for Dickinson, a fact that further reinforces my hypothesis about the connection between mouth breathing and her work. Once, for example, when describing a cold and cough to her friend Abiah Root in a letter, Emily Dickinson eerily personifies her ailment: “out flew my tormentor, and putting both arms around my neck began to kiss me immoderately, and express so much love, it completely bewildered me” (Letters 87). This simple passage shows how Dickinson related to her cough, as if it were something sentient and living. I will present breath and illness as integral parts of Dickinson’s texts.

My conclusion will synthesize how aspects of Dickinson’s life and her writing point to the theory of her being a mouth breather, and the significance of that fact for her poetry. Dickinson’s biography, the manner in which she spoke and wrote, trends found in the dashes themselves over the course of her canon, the manner in which she represents the various senses, and the concept of breath and breathing in the poetry of Emily Dickinson all signify the importance of breath in her life and the possibility of mouth breathing as the origin of the dashes in her poetry. In the following thesis, I encourage the readers to open their minds and listen for the breath of Emily Dickinson conducting the pace of her poetry.

CHAPTER ONE: The Life and Breath of Emily Dickinson

Biographical information about Emily Dickinson is relatively scarce in comparison to that of now-canonical writers of the time. The best information about Dickinson comes from her own hand, in letters and poems, and the hands of those who knew her. As biographer Cynthia Griffin Wolff emphasizes, “Few of the details of Dickinson’s adult life have been recorded; as a result, there are long periods of time—weeks, months, and on one occasion an entire year—for which not even the simplest quotidian activity of her routine can be ascertained” (140). Her sister Lavinia, for example, destroyed the letters written to Emily upon her death, further diminishing the information available about Dickinson. Luckily for us, many of the letters written by Dickinson herself to others survived, as those who corresponded with Emily Dickinson often found her vastly interesting. Even several letters between other individuals about encounters with Emily Dickinson survived. Some of those who knew her, such as her niece, Martha Dickinson Bianchi, even wrote books about their relationship with Emily Dickinson. Other than that, the only other clues about Dickinson’s life come from what is known about the area where she lived.

The biographical information we have about Dickinson however, abounds with references to her breathing. Ordinarily, breathing is an unconscious act. Unless something interrupts it, it is almost unnoticeable. Unfortunately, for Emily Dickinson, breathing was something she was constantly aware of. Her breath, directly or indirectly, is one of the most recorded aspects of Emily Dickinson’s life. Emily Dickinson breathed air for the first time on 10 December 1830. From that point on, it can be said literally and metaphorically that Dickinson’s life was a struggle to breathe. In chapter two, I read the dashes in Dickinson’s poetry as the physical autograph representations of breath in her writing. In this chapter, I set the stage for that reading by focusing on Dickinson’s life.

Dickinson, Breath, and Illness

The basic structure of Dickinson’s life is easily traced, because she resided nearly her entire life in Amherst, Massachusetts. With the exception of a few weeks, spent mostly in Boston, she did not stray at all from her hometown. Unfortunately, however, as Wolff explains, “infant death, the mortal peril of childbirth, consumption, typhoid, strep, pneumonia—all these would continue to haunt Amherst throughout Emily Dickinson’s lifetime” (95).

Disease itself plagued the entire Norcross side of her family. Consumption was especially prevalent in the family of Emily Dickinson. Her mother, Emily Norcross, married into the Dickinson family. Dickinson herself became especially good friends with one of her cousins, Emily Lavinia Norcross. Both of Emily Lavinia’s parents, Amanda Brown and Hiram Norcross, died of consumption. Emily Lavinia followed them in 1842, and her brother, William, died two years after her. According to Woolf, “The disease continued to hound the Norcross family like some inexplicable ancient curse” (60). The respiratory disease of consumption continuously surrounded and penetrated the life of Emily Dickinson.

As I mentioned in the introduction, consumption as an illness is consistent with the presence of the disorder of mouth breathing. While consumption is an infectious disease and thus cannot be inherited, allergies and mouth breathing can be. Those who are forced to breathe through their mouths, because of allergies or malformation, are especially susceptible to catching consumption. While ultimately it is impossible to prove whether the Norcross family was prone to breathing through their mouths, something made them especially sensitive to contracting consumption. This is something that very well could have been passed onto Emily Dickinson through her mother, as an extension of the Norcross curse. Mouth breathing, regardless of what caused it, could have been the reason the Norcross family was so susceptible to consumption.

Dickinson herself suffered symptoms of consumption, referred to as pulmonary tuberculosis today, for most of her life. Even though the disease appears to have been more prevalent earlier in her life, Alfred Habegger emphasizes in one of the most recent biographies of Dickinson that she suffered from “usual seasonal (consumptive?) symptoms” (423) and “her cough persisted and she remained less than ‘stout.’ It would appear that the mysterious wasting disease that killed so many was a constant thorn in her side, and in her mind as well” (262-63).

The possibility of illness was thus a prevalent force in the early life of Emily Dickinson. Her parents were aware of this fact from her childhood. Wolff points out that “throughout Emily Dickinson’s school days both parents worried about her tendency to come down with protracted bouts of flu; often they kept her home from school, sometimes even obliging her to miss an entire term” (68). Dickinson’s parents even at times sent her away, according to Wolff, to escape from the illnesses sweeping through Amherst: “her parents sent her away to visit Aunt Lavinia in Boston (as they had three years earlier after Sophia Holland’s death) to her rid of her ‘cough & all other bad feelings’” (98-9). At times, her father even ordered her to stay home from school when the weather was bad. In a letter to her friend Abiah Root, on 16 May 1848, Dickinson complains about a friend of hers who has informed her parents that she is in ill health. Her parents immediately called her home, much to her dismay: “I could not bear to leave teachers and companions before the close of the term and go home to be dosed and receive the physician daily, and take warm drinks and be condoled with on the state of health in general by all the old ladies in town” (Letters 65-6). After she spent a year of school at Mouth Holyoke Seminary, Dickinson’s father decided not to send her for another year. While the reasons are not known for sure, it is quite likely that her problems with staying healthy had a lot to do with her father’s decision.

Illness is also a constant topic in Dickinson’s letters. She even uses terms relating to medicine or illness, such as “fatigue,” “imbibe,” “indissoluble,” and “hemorrhage,” as verbs and adjectives in her letters to describe how she feels or what is happening around her (see for example letter 261, Letters 404). Emily Dickinson was obviously more aware of the significance of her illness than anyone else, and went to great lengths to understand its relationship with her. Writing to her friend Abiah Root in 1848, Dickinson refers to one of the periods of treatment for an illness: “I was dosed for about a month after my return home, without any mercy, till at last out of mere pity my cough went away, and I had quite a season of peace” (Letters 66). She does not give any credit to the treatments she received; instead, she claims that “out of pity” her cough went away. Dickinson actually refers to the cough, the illness, as something sentient and living.

One particular letter is quite interesting because of the unusual figuration with which it describes illness. I cite at length from her very strange and extended epistolary description of her malady. The trope of personification, one which attributes unusually powerful agency to otherwise inanimate objects, dominates:

I am occupied principally with a cold just now, and the dear creature will have so much attention that my time slips away amazingly. It has heard so much of New Englanders, of their kind attentions to strangers, that it’s come all the way from the Alps to determine the truth of the tale . . . Attracted by the gaiety visible in the street I still kept walking till [the] little creature pounced upon a thick shawl I wore, and commenced riding – I stopped, and begged the creature to alight, as I was fatigued already, and quite unable to assist others. It would’nt get down, and commenced talking to itself – “cant be New England – must have made some mistake, disappointed in my reception, don’t agree with accounts, Oh what a world of deception, and fraud – Marm, will [you] tell me the name of this country – it’s Asia Minor, is’nt it. I intended to stop in New England.” By this time I was so completely exhausted that I made no farther effort to rid me of my load, and traveled home at a moderate jog, paying no attention whatever to it, got into the house, threw off both bonnet, and shawl, and out flew my tormentor, and putting both arms around my neck began to kiss me immoderately, and express so much love, it completely bewildered me. Since then it has slept in my bed, eaten from my plate, lived with me everywhere, and will tag me through life for all I know. I think I’ll wake first, and get out of bed, and leave it, but early, or late, it is dressed before me, and sits on the side of the bed looking right in my face with such a comical expression it almost makes me laugh in spite of myself. I cant call it interesting, but it certainly is curious – has two peculiarities which quite win your heart, a huge pocket-handkerchief, and a very red nose. (Letters 86-7)

To have a close relationship with something such as an illness illustrates the crucial, indeed critical, effect that it had on her. Dickinson animates her illness into a being with its own consciousness. The illness in the above letter is even granted the ability to speak, in addition to many other methods of communication—the symptoms plaguing her. Dickinson is ill to such an extent and for so long that she says it “will tag me through life for all I know,” an apt foreshadowing of what was to come.

Every time someone around her became sick, Emily Dickinson inevitably was cursed with dealing with the illness herself. Writing to her sister over a decade later, Dickinson is aware of a recent bout of illness of her mother, and again uses imagery that makes illness tangible—this time, an object: “Tell Mother to catch no more cold, and lose her cough, so I cannot find it, when I get Home” (Letters 435). The passage indicates that Dickinson was worried about being around other sick people because she so easily caught illnesses that could be passed from one person to another. By this time, Emily Dickinson was thus clearly aware of her special susceptibility to catching illness from others. This tendency, too, is consistent with the effects of mouth breathing, which makes one more prone to catching air-transported illnesses.

Breath and Dickinson’s Voice

Dickinson’s manner of speaking and breathing directly affected her written word. As Brita Lindberg-Seyersted writes in The Voice of the Poet: “Her writing is of the nature of speech also in the respect that, as testified to by observations and evidenced in letters, she wrote as she spoke” (58). While there are always exceptions to the rule, this is an integral observation in understanding both Dickinson’s writing and her use of dashes.

Emphasis on Dickinson’s unusual voice is used to characterize her more than anything else by those who interacted with her. No other single quality, personality trait or otherwise, is described more frequently in first hand accounts of interaction with Emily Dickinson. And, more important, descriptions of her voice very often emphasize the strangeness of her breath. In August of 1870, for example, T. W. Higginson, frequent correspondent and, famously, mentor, wrote home to his wife when he was visiting Dickinson at her Amherst residence. His letter to her has become one of the most renowned and often quoted passages used to describe Emily Dickinson. He recounts meeting Dickinson:

A step like a pattering child’s in entry & in glided a little plain woman with two smooth bands of reddish hair & a face a little like Belle Dove’s; not plainer – with no good feature – in a very plain & exquisitely clean white piqué & a blue net worsted shawl. She came to me with two day lilies, which she put in a sort of childlike way into my hand & said, “These are my introduction” in a soft frightened breathless childlike voice – & added under her breath, Forgive me if I am frightened; I never see strangers & hardly know what to say. (Qtd in Leyda 151)

Higginson describes Dickinson’s voice, what she said, and the fact that part of what she said was both “breathless” and “under her breath.”

Other accounts almost exactly match Higginson’s in their stress on Dickinson’s oddly “breathless” voice. Martha Dickinson Bianchi, Emily Dickinson’s niece, in her book Emily Dickinson Face to Face, begins by describing Dickinson’s voice as “breathless in turn” (17). In another similar account, Clara Green, who met Emily Dickinson with her sister Nora and her brother Nelson, describes Dickinson’s voice almost identically: “She spoke rapidly, with the breathless voice of a child and with a peculiar charm I have not forgotten” (Leyda 273). These three descriptions of Emily Dickinson’s voice provide an interesting portal into understanding how Dickinson spoke conversationally.

The breathless voice of Emily Dickinson could indicate the effect that mouth breathing had on her speech. The key connection between these “breathless” descriptions and mouth breathing might well lie in another passage from Bianchi’s Emily Dickinson Face to Face. Bianchi describes something Emily Dickinson said: “‘Would Matty like to have a pussy of her own to take home and keep always?’—adding with a catch in her breath—as their lawful owner was upon us—‘Take more than one! Take them all! Don’t stop to choose, dear!’” [emphasis mine] (7). Thus it seems that Emily Dickinson’s speech rhythms were fundamentally characterized by her need so often to stop and catch her breath when talking—enough to merit its crucial repeated attention by those around her, and even mention within a quotation of Dickinson’s very words as part of something she said by her niece.

However, when she recited poetry or read other works out loud, something different happened. While it appears that Dickinson spoke in conversation rapidly, a contrast seems to exist with her manner of reciting poetry or reading other works out loud. Habegger, in his biography, highlights a portion of a 1895 essay, crediting the earlier find to Mary Loeffelholz, which elaborates on Emily Dickinson as a reader:

Emily was herself a most charming reader. It was done with great simplicity and naturalness, with an earnest desire to express the exact conception of the author, without any thought of herself, or the impression her reading was sure to make. (398)

From this passage, it appears Dickinson took her time reading out loud. The description of her reading in this passage is not consistent with the descriptions of her rapid and out of breath conversational speaking.

That change of pace could very well have been quite deliberate. Mouth breathers are often aware of the irregularity in their breathing and especially its effect on the pace of their speech, either consciously or not. Reading out loud was a common and important performative gesture during the period when Dickinson lived, thus she would have had both exposure to and experience in reading to others. This awareness would likely have caused her purposefully to slow her speech in order properly to represent texts with punctuation foreign to her natural breathing patterns. Dickinson’s own poems would be read slowly precisely because the punctuation would match her slow reading and breathing patterns.

The distinction between the way Emily Dickinson spoke conversationally and the way she read poetry out loud might also explain the different frequencies of dashes found in her letters and poetry. Both the letters and the poems contain an unusual number of dashes, a gesture I am associating with irregularity in her breathing. Her letters contain few dashes, thus indicating fewer pauses, making their pace quicker and more like how she spoke conversationally. Accordingly, then, perhaps Dickinson’s poems have more dashes than her letters because she would have imagined them as being read more slowly, just as she spoke more slowly and deliberately when reciting poetry. Interestingly, as we shall learn in the next chapter, both her letters and poems conform to the same dash frequency patterns found in her writing over the course of her life, even though her use of dashes in each fundamentally differs.

Breathing with Others

Dickinson transformed the works of others in order to adapt their work to her breathing and language patterns, by punctuating the works of others with dashes where she needed them. When reading the work of others out loud, Dickinson needed to be aware of her breathing so she could account for its discrepancies with the punctuation of the writer. The punctuation that came so natural to her writing was not present in the works of others. In one example, Dickinson inserted dashes when copying the work of George Herbert, as Franklin points out in The Editing of Emily Dickinson: A Reconsideration (121). In fact, in their 1945 collection of Dickinson’s poetry, Bolts of Melody, Dickinson’s niece and Dickinson’s brother Austin’s paramour mistakenly published this portion of a Herbert’s “Mattens” as Dickinson’s own, thinking her transcription of the poem was an original composition because she had applied her own unique form of punctuation when copying it (125).2

This transcription shows how her use of punctuation was something inherent in her. In the second to last line of the poem, Dickinson even changed the properly spelled word “upon” to the way she spelled it her entire life, “opon.” The original two stanzas taken from George Herbert’s “Mattens” and Dickinson’s copy are as follows:

My God, what is a heart?

Silver, or gold, or precious stone,

Or starre, or rainbow, or a particular

Of all these things, or all them in one?My God, what is a heart?

That though shouldst it so eye, and wooe,

Powring upon it all they art,

As if that though hadst nothing else to do?Second and Third stanzas from “Mattens” by George Herbert (1633)

My God – what is a Heart,

Silver – or Gold – or

precious Stone –

Or Star – or Rainbow –

or a particular

Of all these things – or

all of them in one ?My God – what is a Heart –

That though should’st it so

eye and woe

Pouring opon it all thy

art

As if that though had’st

nothing else to do –Copy by Emily Dickinson

Dickinson’s copy of the two stanzas of the poem actually retains the same lineation as the original. When Dickinson ran out of space, she moved to the next line and indented it to show it was still part of the same line. The copy above represents the actual autograph spacing used by Dickinson, and her lineation will be explored further in chapter two. For now, what is important to notice is that Emily Dickinson replaced Herbert’s punctuation with her own, changed the spelling of some words, and even replaced the word “Powring” with “Pouring.” These changes show that Dickinson transformed the punctuation of the works of others to meet her breathing needs, primarily by adding space for breath through the addition of dashes.

One of the most telling examples of how Emily Dickinson was interpreted by others during her day comes from her early correspondence with T. W. Higginson. After reading an article in the Atlantic Monthly entitled “Letter to a Young Contributer” by T. W. Higginson, Emily Dickinson decided to write him a letter on 15 April 1862. The letter shows a number of different things, so I begin with a transcription of the short letter itself:

Mr Higginson, Are you two deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?

The Mind is so near itself – it cannot see, distinctly – and I have none to ask –

Should you think it breathed – and had you the leisure to tell me, I should feel quick gratitude –

If I make the mistake – that you dared to tell me – would give me sincerer honor – toward you –

I enclose my name – asking you, if you please – Sir – to tell me what is true?

That you will not betray me – it is needless to ask – since Honor is it’s own pawn –

(Letters 403)

The most interesting portion of the letter is Dickinson’s asking Higginson if her “Verse is alive,” if “it breathed.” In a very crucial moment, Dickinson herself clearly and fundamentally associates her poetry with breathing.

In a letter responding to Higginson, Dickinson gives many clues of his reaction to her poetry. His actual response to her inquiring mind is not directly available, because it had most likely been burned by Dickinson’s sister Lavinia. It appears that his reception of her poetry was not immensely positive, considering the reaction she has to both his criticism and praise. First Dickinson uses the discourse of illness in description of the correspondence: “Perhaps the Balm, seemed better, because you bled me first” (Letters 408). Dickinson goes on, explaining his reaction further: “I smile when you suggest that I delay “to publish” – that being foreign to my thought, as Firmament to Fin –” (Letters 408). Then, she moves to language that stresses Higginson’s reaction to Dickinson’s irregular, unusual rhythm:

You think my gait “spasmodic” – I am in danger – Sir –

You think me “uncontrolled” – I have no Tribunal

(Letters 409)

This portion of the letter, expressed quite prosaically—if not poetically—opens the door to Higginson’s reaction to her poetry. As mentioned previously for effect, it can be inferred that Dickinson asked if her verse breathed, and Higginson replied by calling her gait “spasmodic.” Higginson, likely a nose breather, would be distracted by Dickinson’s dashes, as many modern readers and scholars are. This explains his response to her poetry, more specifically the dashes that interrupted his gait, not Dickinson’s.

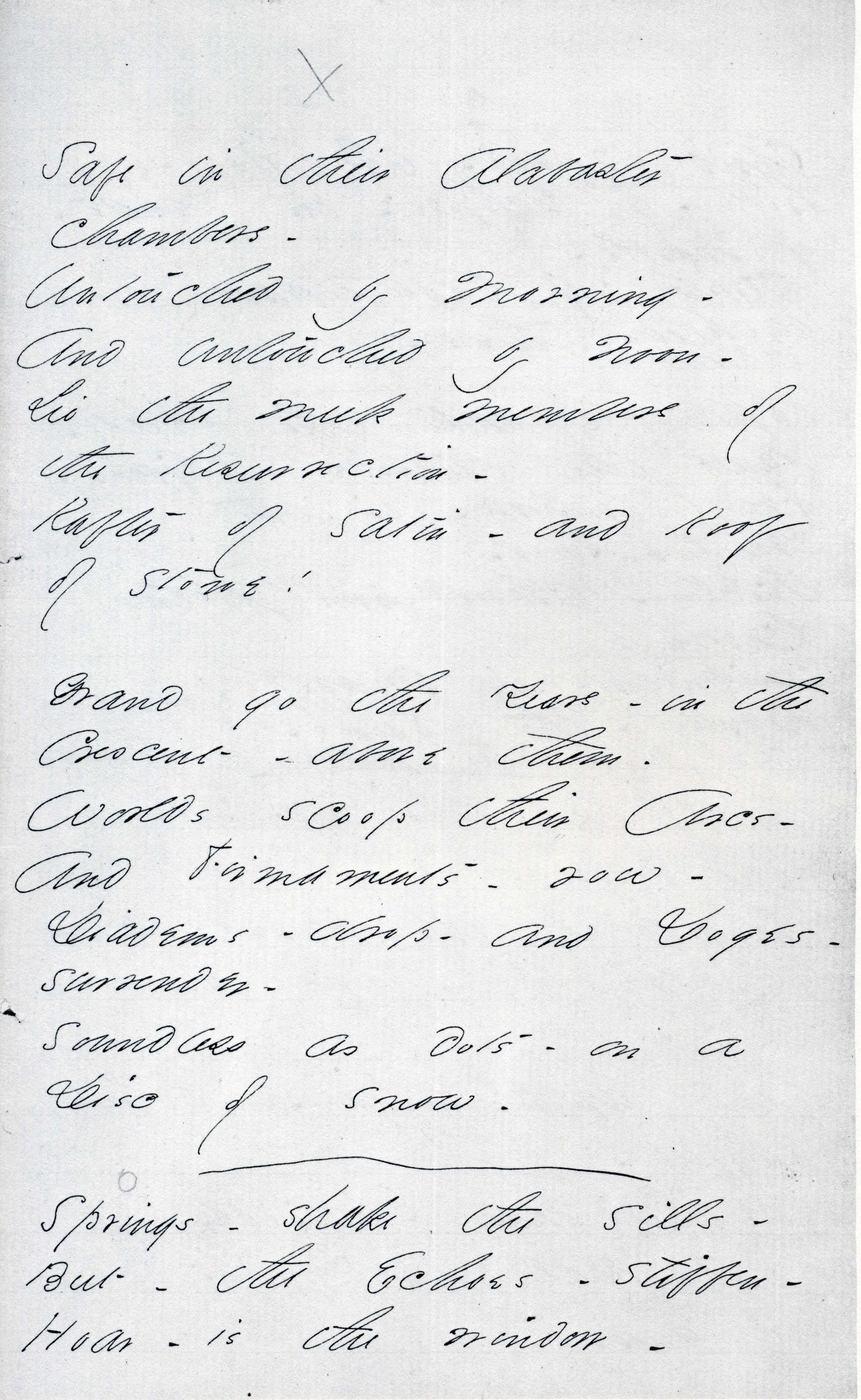

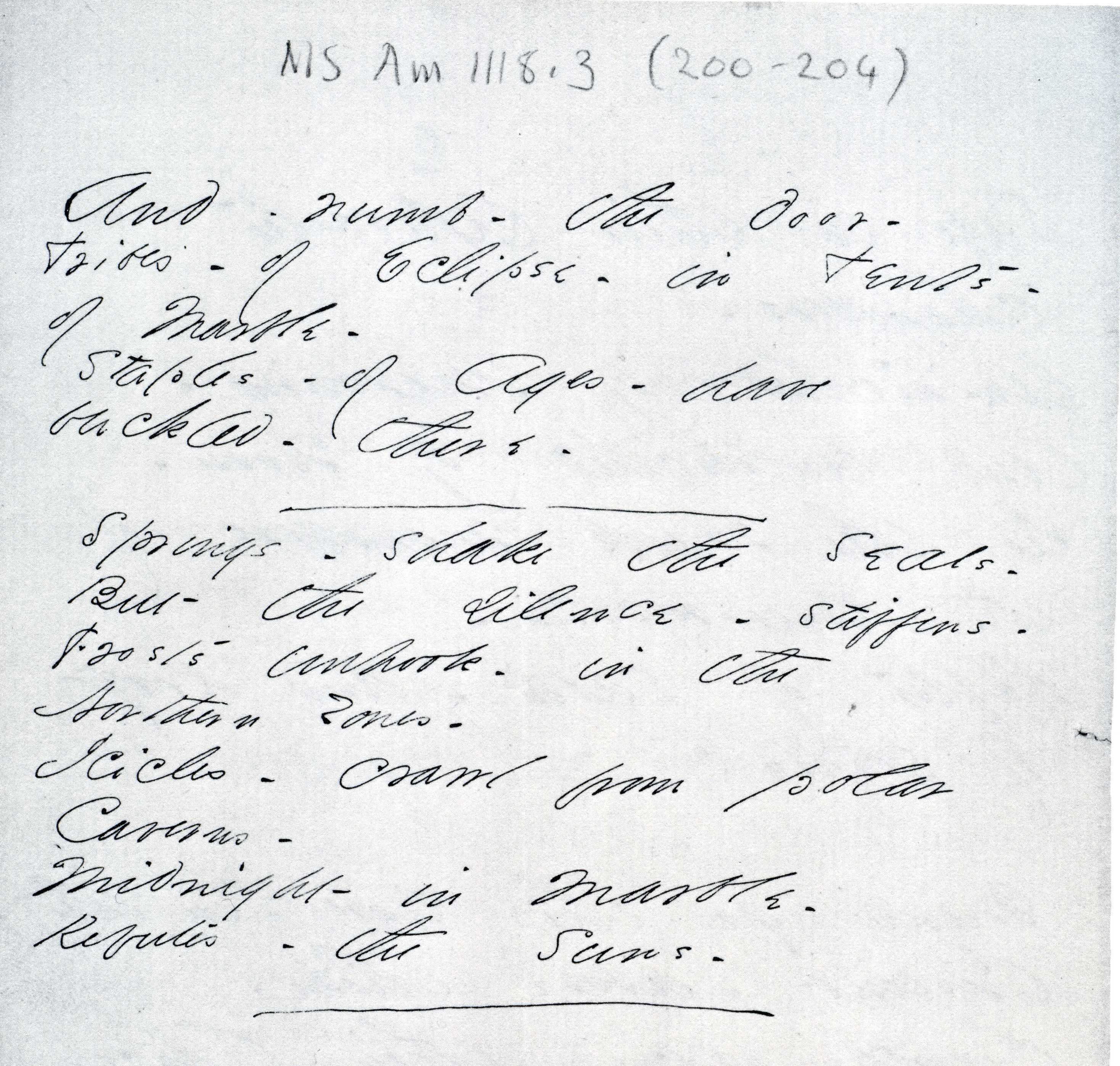

Dickinson’s Alabaster Chambers

With her first letter to Higginson, Dickinson included both a card with her signature, and four different poems. One of the poems she included was “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers.” Emily Dickinson’s poem “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers” is unique in that so many versions of it exist, opening a door that enables readers to witness the progression of her craft over a short, yet crucial, period of time. Some time after 1861, when the final completed version of this poem was scribed into her fascicles, Emily Dickinson responded to a letter which today does not exist. She was writing a reply to her sister-in-law Susan Dickinson, with whom she had a vast correspondence during her lifetime. She asks Susan, “Is this frostier?” (Franklin 161). Dickinson is referring to a poem she initially wrote in 1859, in which the first line, “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers –” remained unchanged in all its incarnations. Immediately following the one-line question came another version of the second stanza that greatly differed from both the 1859 and 1861 versions of poem 124. The 1859 version of “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers” is more than a rough draft of the final poem, though. Dickinson destroyed almost all of the original drafts of her poems, so it is crucial to pay attention to how she changed the few poems which are not forever dormant in their final fascicle form.

The drafts of this poem provide important understanding to the evolution of both Dickinson and her poetry during one of the most important times in her life, when she began copying her poems into fascicles bound with string. The first stanza remains similar in all versions of the poem, but the second stanza, due to the critique of the initial poem by Susan, was changed by Dickinson again and again. While the second stanza of the poem was rewritten several times by Dickinson, the first two versions cataloged by R. W. Franklin as poem 124 exemplify a vast change in the poetry of Emily Dickinson. I want to emphasize that the drafts illustrate an important general trend: During the progression of this poem, Emily Dickinson began using her characteristic dashes more frequently. The shift from the often ignored 1859 version of the poem to the more vast 1861 variant shows a more mature wisdom that can only be expected to shine from such a unique individual during the progression of her craft.

Two versions of the first stanza of the poem exist, showing a subtle syntactical change that represents a vast metaphorical fissure in the life of Emily Dickinson. Susan Dickinson, writing about the first stanza, told Emily: “I always go to the fire and get warm after thinking of it, but I never can again” (Franklin 161). Both of the versions of the poem begin with a very similar stanza. The change in the lineation is the most visible difference between the two versions, but it does not change the meaning of the stanza:

Safe in their Alabaster Chambers –

Untouched by Morning

And untouched by Noon –

Sleep the meek members of the Resurrection –

Rafter of satin,

And Roof of stone. (Fr124B)

version of 1859Safe in their Alabaster Chambers –

Untouched by Morning –

And untouched by Noon –

Lie the meek members of the Resurrection –

Rafter of Satin – and Roof of Stone! (Fr124E)

version of 1861

Ignoring the use of dashes for a moment, the only substantive difference between the two is the substitution of the word “sleep” with the word “lie” in the fourth line. The substitution of this word shifts the image from the dead as sleeping, or waiting for resurrection, to the dead as entirely inanimate—perhaps forever. Dickinson questions religion and the existence of God and an afterlife often in her poetry, which shows how such a small shift in language is actually very important to her. If the corpses are sleeping, we expect them to awake; if they just lie in their tombs, then they could remain forever dead and the suggestion of resurrection would be ironic.

Dickinson’s use of dashes is adapted into the dominant form of punctuation in her poetry sometime in the early 1860s. This transformation is exemplified by the 1859 and 1861 versions of the second stanza of “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers” (Fr124), represented here:

Light laughs the breeze

In her Caster above them –

Babbles the Bee in a stolid Ear,

Pipe the Sweet Birds in ignorant cadence –

Ah, what sagacity perished here!

version of 1859Grand go the Years – in the Crescent – above them –

Worlds scoop their Arcs –

And Firmaments – row –

Diadems – drop – and Doges – surrender –

Soundless as dots – on a Disc of Snow –

version of 1861

While it is important to take in account all variants of each Dickinson poem, these two versions of the second stanza embody the evolution of Dickinson’s craft. In 1862, it is believed Susan Dickinson attempted to publish a version of this poem, one very similar to the 1861 version, so it is possible that Emily Dickinson was rewriting this poem up to a few years after the initial two versions (Franklin 164).

By looking at the variant final stanzas written, we can see clearly that Dickinson had a rhythm which remained prevalent through years of writing and rewriting “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers” (Fr124). Even considering an increase in the use of dashes over the course of the writing of this poem, the rhythm of the words themselves, if the dashes were removed entirely from both versions, remains unaltered. The introduction of more dashes does however slow the pace or tempo of the poem, but does so without interrupting the rhythm of the words. In fact, similar rhythm is quite common—even inherent—in all of Dickinson’s poetry. The increase in the use of dashes is thus independent of the rhythm of the language in her poetry, and serves only to alter the pace of a structure inherent in both her writing and speaking.

The different versions of “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers” (Fr124) diverge in their relation to the world as well, indicating a shift in Dickinson’s relationship to the world. The 1859 version of the second stanza is confined to the world immediately above the cemetery in the poem. The wind blows in the Castle (the sky) above the graves, a bee is buzzing about, birds are singing, and sagacity, the wisdom of all who lie in the cemetery, is gone. The main difference between the two poems is the vastness outside of the cemetery expressed by Dickinson and, more than likely, the time of day. The 1861 version of the poem is vast, speaking about worlds moving and stars rowing across the sky, which can only been seen at night. The second stanza also includes the fact that kings die and magistrates fall, and they are no different from anyone lying in the graves of this cemetery.

The trials and tribulations of completing “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers” parallel the struggles of Emily Dickinson in the early 1860s. In a letter to Dickinson, Susan Dickinson tells her that she is not “suited dead” with the second stanza. Half-way through the letter Susan has an epiphany of sorts: “It just occurs to me that the first verse is complete in itself and needs no other, and can’t be coupled—Strange things always go alone—as there is only one Gabriel and one Sun—You never made a peer for that verse, and I guess you[r] kingdom doesn’t hold one” (Franklin 161). Unfortunately, even with several rewrites, including the wonderful 1861 version, Emily was never able to please Susan Dickinson with a second stanza, as evidenced in their correspondence. Something which remains unknown today, sometime around 1865, caused Dickinson to cease her efforts to have her poetry published, caused her to stop binding her fascicles with yarn, and kept her from ever returning to work on this wonderful poem.

Strange Things Always Go Alone

The composition of “Safe in their Alabaster Chambers” (Fr124) highlights an important transitional period in the life of Emily Dickinson. Scholars have long reminisced about a single cataclysmic event in Dickinson’s life that occurred somewhere in her mid twenties to mid thirties (1855-1865). Little is known about Dickinson during this time, especially during the last half of the 1850s. The years 1855-58 are veiled in complete mystery, as Habegger explains:

The documentation of her life in these years is so slender that some have concluded she had an incapacitating and well-covered-up breakdown, perhaps even a fully psychotic episode . . . That she experienced severe and mounting troubles is clear. That she became any less capable of performing her usual functions, domestic and compositional, is not. The sharp reduction in the number of her surviving letters has several explanations: most of her earlier friendships had lapsed; and with Sue and Austin settling in next door she had no occasion to produce the detailed record of the early 1850s. Most important, her continuing shift from reportorial to lyric modes tended to throw another veil over her life, the thickest one yet. To an extent, she disappeared into her poems, which, in 1858, apparently without telling anyone, she began preserving in small, neatly copied, hand-sewn booklets. Increasingly, her bulletins would come from a place no one we know had seen or visited. (327) The only known “severe and mounting troubles” in Dickinson’s life include the ever-persistent problems with illness and a bout of severe eye trouble that she encountered during this time. However, these issues can more than likely be placed after 1858. Illness was always a force of reckoning in the life of Emily Dickinson, but the elevation in her dashes from 1861-64 may signify the most severe problems she encountered—especially if the dashes in her poetry represent breath. The eye troubles seem to become severe during the same period, and they appear to be resolved in the final year Franklin attributes a great number of poems to, in 1865. Thus, something else must have been responsible for Habegger’s observation.

Martha Nell Smith associates the troubles Habegger mentions with the loss of love. In Rowing in Eden: Rereading Emily Dickinson, Smith postulates that Dickinson was in love with Susan Gilbert, the woman who married her brother Austin in 1856. In one of many letters to Susan before she married her brother, Dickinson writes, “I think of love, and you, and my heart grows full and warm, and my breath stands still” (Letters 201). Smith has found that the letters to Susan Gilbert from Emily Dickinson have been altered—pieces were deliberately cut from them in order to mask their true intentions. Smith believes the culprit to be Austin Dickinson, as she writes in Rowing in Eden: “the censorship of Dickinson’s papers at the end of the century suggests that her passionate friendship with Sue was not simply innocent” (23). If this is true, the severe problem Dickinson may have encountered during this time was the loss of a love and an inadvertent betrayal by her brother. What made matters worse is that Austin and Susan ended up living across the street from Emily Dickinson.

As the 1860s appear, more evidence and history exists to shed light on Emily Dickinson, but the poems she writes complicate the understanding of her even more. There is a good chance that the number of poems scribed in the fascicles during this time is from Emily Dickinson copying prior poems in addition to writing new ones. I believe Dickinson may have thought that she was dying at the turn of the decade from the 1850s to the 1860s, and this could be the reason for the great number of poems attributed to these years. Regardless of what afflicted her, it seems that Dickinson was preparing her poetry for the inevitable coming of death. This would explain the vast quantity of poems attributed to the early 1860s, when she most prolifically copied poems into fascicles and bound them with string. Unfortunately, Dickinson destroyed the original drafts of her poems after copying them into the fascicles. There is a good chance that much of what she copied into the fascicles in the early 1860s could have come from a prior time. During this same time, in the early 1860s, Alfred Habegger finds that the subject of pain becomes prevalent in the poetry of Dickinson. Habbegger writes in his biography of Emily Dickinson:

The idea of extreme pain, appearing in a few poems in 1859, became one of Dickinson’s major subjects in the early 1860s. Of the twenty-one instances of the word “hurt” in her poems (noun or verb), every single one occurs between 1860 and 1863. The apparatus of torture—“grimblets” (Fr242), “metallic grin” (Fr243), “A Weight with Needles” (Fr294)—now becomes almost routine, along with references to Jesus’ betrayal and crucifixion, generally linked to the speaker’s own passion.” (408)

The extreme pain that he talks about could have been pain from the union and betrayal of her possible lover Susan Gilbert and her brother Austin. During this period of time, from 1861 to 1864, it cannot be ignored that something else was going on, though. The extreme increase in the frequency of dashes in both Dickinson’s poems and her letters must signify something.

The poems attributed to the years 1861 through 1864 are all also very similar in their use of dashes, possibly linking them to the pain mentioned above. As my research in chapter two shows, these four years have twice the amount of dashes as any other year in Dickinson’s life, and, I believe, they also represent most of the years in which nearly half of her poems were copied into her fascicles. If the dashes of Emily Dickinson’s poetry are representative of her breath, then something caused the need for her to breathe more frequently than ever. This is something that could be explained by her consumption or other illnesses during this time, or quite simply the need to breathe through her mouth because of allergies. Regardless, life may have been so dismal that she did believe her death was imminent, and thus resigned herself to copying the poems into her fascicles during these years. In addition, when copying the poems, she probably read them out loud to herself, as was customary during the time. If so, she would have found a need for more dashes in her poetry due to her current illness. Even if she did not read them out loud, her natural rhythm still could have been fundamentally altered by her illness and need to breathe more often. This is why all of the poems, those that she probably copied and even those that she wrote during these four years, have a greater frequency of dashes. It is not likely that she used this many dashes when originally writing these poems. In the few final years of the 1850s, the poetry that is dated shows no signs of an elevated use of dashes. By the time 1865 arrives, the use of dashes in the poetry of Emily Dickinson once again dissipates to pre-decade levels. It only ever rises again toward the end of her life, when she wrote less and less.

Wearing Alabaster

After 1865, the stories that have generated the myths of Emily Dickinson start to take shape. By this time she is thirty-five years old. The largest myth about Emily Dickinson is that she never left her house and spent her entire life indoors. She experienced life outside of her house for thirty-five years, though, and she even reminisced about it in letters to those with whom she corresponded:

How glad I am that spring has come, and how it calms my mind when wearied with study to walk out in the green fields and beside the pleasant streams in which South Hadley is so rich! There are not many wild flowers near, for the girls have driven them to a distance, and we are obliged to walk quite a distance to find them, but they repay us by their sweet smiles and fragrance. (Letters 66)

Dickinson herself kept an herbarium, in which she gathered the flowers that she found on her walks and pressed them into a single volume. She even asked her friend Abiah Root if she had an herbarium, claiming that “it would be such a treasure to [her]” (Letters 13). In the end, Dickinson’s own herbarium housed specimens of over four hundred pressed flowers. Yet, even with such a love for nature, after spending the summer of 1865 away, “Emily Dickinson returned to Amherst in October. She lived for more than twenty years but never again left home—that home which to her was “the definition of God” (Bingham 437).

Emily Dickinson began exclusively wearing white sometime around the early to mid 1860s. According to Habegger: “Exactly when the poet began wearing white year-round isn’t known. In December 1860, as if putting a stop to rumor, she pointedly asked Louisa Norcross to “tell ‘the public’ that at present I wear a brown dress” (516). Habegger even points out a poem in which Dickinson writes about wearing white:

A solemn thing – it was – I said –

A Woman – white – to be –

And wear – if God should count me fit –

Her blameless mystery –A timid thing – to drop a life

Into the mystic well –

Too plummetless – that it come back –

Eternity – until –I pondered how the bliss would look –

And would it feel as big –

When I could take it in my hand –

As hovering – seen – through fog –And then – the size of this “small” life –

The Sages – call it small –

Swelled – like Horizons – in my breast –

And I sneered – softly – “small”! (Fr307)

This poem, attributed to 1862 by Franklin, emphasizes the individuality of Dickinson. She seems to have chosen a life of solitude, not to marry, and ponders how this will be perceived by others, by God. In the end, a confident Emily Dickinson appears, sneering at those that will deem her life small. It is interesting how right she is in this poem, as her thoughts, their words and breath, are now immortalized forever. Whatever the reason for wearing white, by the time she was wearing it daily, Emily Dickinson was in such a reclusive state that her sister Lavinia, who was roughly the same size as Dickinson, was fitted for her sister Emily’s dresses. Dickinson’s myth only spread as she retreated into the confines of her father’s house and dressed wholly in white. Even the coffin she would be buried in was white.

On 13 May 1886, Emily Dickinson slipped into unconsciousness. “The next day Austin noted that his sister’s stertorous breathing had gone on for a full day: ‘Emily is no better—has been in this heavy breathing and perfectly unconscious since middle of yesterday afternoon’” (Habegger 626). The following day, 15 May 1886, as noted again by Austin, Emily Dickinson “ceased to breathe that terrible breathing” (Habegger 627). Bianchi recorded how young she looked in her final chamber, in Face to Face: “Her deep Titian hair never got a grey thread. Her white skin never showed a blemish, its lack of color unnoticeable . . . Age never benumbed her” (67). Emily Dickinson was adorned in a white dress and robe, placed in a white wooden coffin, and buried in the cemetery of Amherst beneath a white gravestone.

Originally, it was concluded by doctors that Emily Dickinson died of Bright’s Disease, a common diagnosis during that time in the New England area. Habegger, however, mentions something very interesting. Drawing on the authority of Dr. Norbert Hirschborn and Polly Longsworth, he writes:

The true cause of death, they argue, was severe primary hypertension, a diagnosis not available in 1886. This explanation seems consistent with the known facts in the case: the stress under which the poet lived; the emotional effects of her bereavements; the state of medical science at the time; and the record of symptoms in her last two and a half years, thinking particularly of her bouts of fainting and final stroke. (Habegger 623)

As shown in the Introduction, mouth breathing raises the pH balance of the blood, and causes hypertension. Mouth breathing may have been the specter haunting Dickinson her entire life, its hooded gasp showing itself proudly at her end.

The dashes in the poetry of Emily Dickinson represent her breath. Breathing, or more importantly trouble with breathing, is abundant in the biography of Emily Dickinson. Her voice itself was representative of her breathing and, as shown in this chapter, she wrote as she spoke. This is further evidenced by the fact that she manipulated the written works of others in order to fit them to her own breathing patterns. Even her own mentor, T. W. Higginson, did not understand the intricacy of breathing inherent in her life and represented in her poetry, and he experienced it first hand. The theme of breathing is not simply something in her biography, though. Emily Dickinson’s life and death were a struggle to breathe, and this had a great effect on her writing.

CHAPTER TWO: Conducting Emily Dickinson’s Dashes

Emily Dickinson’s formidable canon of verse (almost 1800 poems) and letters spans a massive array of subjects, both physical and metaphysical, and represents one of the most important bodies of literature we have. Unfortunately, Emily Dickinson is also one of the most misunderstood American authors. Her poems are exceptionally dense, especially given their brevity. In addition, we still grapple with what to make of her odd punctuation, especially the dashes. We still do not know how to read them. Current scholars generally read them in ways that literally take away from the aural quality of Dickinson’s poems in an attempt to find meaning through a visual acuity that serves to be at best incomplete.

Emily Dickinson’s autograph script is a main point of contention among contemporary scholars. The manuscripts themselves have generated much debate as the interpretation of the physical characteristics of her script, especially slight variations found in her dashes, have arisen a multitude of suspicions as to purpose of the dashes. Interpretations of her use of space, lineation, and word division have only complicated the poems of Emily Dickinson further.

The handwriting of Emily Dickinson might well express her irregular struggle to breathe through her especially elaborate use of dashes in her writing. When one is reading the poetry of Emily Dickinson, it is as though her breath can literally be heard weaving in and out between the words of her verse. Trends in her writing, in the frequency of dashes that appear in both her poetry and letters, weave into the history of her life. It is likely that the simple reality behind her use of dashes and the attributes found in her handwriting both derive from the result of natural phenomenon. The variations found in her script are nothing more than the natural result of normal fluctuations of pen movement in handwriting. The dashes—the singular most visible aspect of the poetry and letters of Emily Dickinson—generate more of a pause for breathing than conventional punctuation such as periods and commas, which is precisely why Dickinson needed them to match the natural rhythms of her own speech, ones consistent with those of a mouth breather.

Modern Dickinson Scholarship

In recent years, scholarship has increasingly moved toward examining the manuscripts themselves, because of the unique features found in the autograph script of Emily Dickinson. Unfortunately, the observations of Dickinson’s handwriting impede the the understanding of her poetry by emphasizing the dashes as something unique and separate from the natural phenomenon of handwriting and the breath that generated them. Lindberg-Seyersted observed in 1968:

It would seem probable that a careful study of the poet’s manuscripts would make it quite clear what punctuation marks she actually used. This is not so, as everyone knows who has tried to decode these sheets of notepaper, scraps of paper, bits of envelopes. The conventional signs she used were the period, question mark, exclamation point, and comma; besides these there is a variety of marks of varying lengths and slants which have generally been referred to as “dashes.” (184)

Reading Dickinson’s poems in her own hand has led many scholars to interpret the poems in a variety of new ways, especially surrounding her use of dashes. Unfortunately, throughout the history of Dickinson scholarship, the more her dashes are explored, the more complex are the explanations that arrive for their existence and their purpose. Considering the length and breadth of Dickinson’s canon, future scholarship has the possibility to confuse the matter even more. The problem is that scholars generally focus on individual aspects of Emily Dickinson’s autograph script, instead of observing them as a part of a handwriting whole.

Even after decades of debate, the dashes still remain as one of the more controversial points in Dickinson scholarship. In Inflections of the Pen, Paul Crumbley argues that Dickinson’s dashes serve an integral purpose in generating voice shifts, and he provides a very compelling argument for this theory. He represents the dashes in Dickinson’s poetry with sixteen different print marks. Crumbley’s marks are meant to indicate dashes of different lengths, at different angles, and at different positions above and below the line of writing. Crumbley claims that the different dashes “contribute to the tension felt by the speaker in addition to disrupting the syntax” (57). In addition, he mentions that more print versions of dashes may be needed to accurately represent all of the different dashes of Emily Dickinson’s poetry. Crumbley’s interpretation of the differing dashes of Emily Dickinson is an example of how her dashes continue to be visually manipulated into an increasing number of generally confusing interpretations.

The opposing view is buoyed by the scholars who have spent the most time with Dickinson’s actual manuscripts, Thomas Johnson and Ralph W. Franklin. They argue that one dash is no different from any other dash, regardless of slight variations found in their appearances. Franklin shares his experience with the manuscripts in the following passage from his 1967 book The Editing of Emily Dickinson: A Reconsideration:

Familiarity with the manuscripts should show that the capitals and the dashes were merely a habit of handwriting and that Emily Dickinson used them inconsistently, without system. . . . Frequently several autograph copies of the same poem exist, each with variant punctuation and capitalization . . . That the capitals and dashes were merely habits of handwriting without special significance is also shown by the poet’s using them not only for poems but for letters too. (120)

Christanne Miller concurs with their observations in her essay, “Dickinson’s Experiments in Language,” in The Emily Dickinson Handbook. Miller writes: “years of teaching Dickinson have convinced me that the unusual features of her work lend themselves to overinterpretation, providing eager critics with the opportunity to see every mark and syllable as individually deeply significant” (255). This is especially true about the dashes themselves. Long have Dickinson scholars attempted to explain and bring meaning to the unusual punctuation inherent in both her poetry and letters.

What is even more baffling than the many ways the dashes of Dickinson can be interpreted is the origin of the dashes themselves. In The Editing of Emily Dickinson: A Reconsideration, Franklin mentions that Edith Perry Stamm believes the dashes to originate from practices taught at Amherst Academy and that they indicate voice inflection (119). Franklin adequately debunks this theory, but does not provide any explanation for the origin of the dashes in Dickinson’s poetry himself. The stanza form commonly employed by Dickinson led some scholars to believe that it was derived from hymns, so the dashes were possibly musical devices of some sort. Few scholars, however, are content with this explanation, as there is very little proof to support it beyond the form of the poems themselves. The vastness of Dickinson’s canon provides many new ways to interpret her poems, but without knowing the origin of the dashes, it is hard to support any special theory about their purpose.

Emphasizing the Rare

Many scholars focus on other strange and rare occurrences found in the manuscripts of Emily Dickinson and draw conclusions based on them, further emphasizing the manner in which Dickinson’ script impedes the understanding of her poetry and its form. One such occurrence is the division of the word “Countrymen” in the poem “This is my letter to the World” (Fr519). This is one of the few instances where Dickinson splits a word in half across lines, when it seems that she should have simply moved the entire word to the following line. When this was found, scholars quickly found a few other instances where this occurs. Some believed that Dickinson’s poems were perhaps not represented accurately in Franklin’s 1998 edition of poems, and that the lineation found in the manuscripts should be precisely preserved. Franklin and Johnson have concluded that Dickinson used the normal convention of extending a single line across two lines, by indenting the portion of the line that extends past the space available on the next line, when running out of writing space. This has been challenged by modern Dickinson scholars, though.

Martha Nell Smith brings up the unconventional possibilities of Dickinson’s lineation in her wonderful book Rowing in Eden: Rereading Emily Dickinson. Smith talks about another well-discussed poem dealing with lineation: “One need not be a Chamber – to be Haunted –” (Fr407). When looking at the photostat of the poem in Franklin’s The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson, Smith’s point that the division of the word “Apartment” is purposeful appears to be quite valid. She represents the third stanza of the poem as follows, showing the split of the word “Apartment” near the end of the stanza:

Ourself behind Ourself –

Concealed –

Should startle – most –

Assassin – hid in Our Apart-

ment –

Be Horror’s least – \ (Fr407)

Smith explains: “What we expect is not what we get: the unanticipated mid-syllable line ending, not haphazzard, is a deliberate breaking of form” (19). This, however, is not an experiment in lineation.

Smith’s observation is not repeated in the other variant of “One need not be a Chamber – to be Haunted –” (Fr407). As I discussed in chapter one, even though Emily Dickinson copied poems and destroyed the original drafts, several variants of the same poem sometimes still exist because she often sent letters with poems. The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson only include photostats that were found in the fascicles themselves, and they do not include versions of poems sent to correspondents in the letters of Dickinson. Another version of this poem exists, sent to Susan Dickinson a couple of years after it was scribed into the fascicles. When comparing the two versions of the poem, we find differences that show that Dickinson was not deliberately breaking form. The first line of the stanza is split at a different place: “Ourself behind / Ourself, Concealed –” Franklin considered this to be one line and, considering the small but noticeable indentation of the second line, it seems that convention holds true and this line should be considered as one. As for the splitting of the word “Apartment,” it does not occur in the identical poem sent to Susan Dickinson. While the word is physically split at the letter t in the middle of the word, it is apparent that it is not split by a dash or a division in the word, but simply by the mark that is supposed to cross the letter t. Smith fails to represent Dickinson’s indentations in her print version of the stanza in Rowing in Eden. The significant indentation represents that the last syllable of the word “Apartment” actually belongs to the prior line. While I do not agree with Smith on the division of the word “Apartment,” I must applaud her contributions to Dickinson scholarship.

Proof that the strange lineation in Dickinson’s manuscripts is not intentional ironically comes from her own hand. In a letter to Susan Gilbert (Dickinson) in 1852, Emily Dickinson proclaims her disdain for paper:

Susie, what shall I do – there is’nt room enough; not half enough, to hold what I was going to say. Wont you tell the man who makes sheets of paper, that I hav’nt the slightest respect for him! (Letters 184)

Emily Dickinson was thus aware of the lack of space provided by the paper she wrote upon, furthering the proof that she did not experiment with lineation but was bound by the confines of the page itself. As Dickinson aged and her autograph script became larger and larger, she would have become even more aware of the problems of space as the paper she used did not become any larger. The rest of the proof that Emily Dickinson did not purposefully generate differences between dashes and experiment with lineation comes directly from her handwriting itself.

Trends in the Poetry of Emily Dickinson

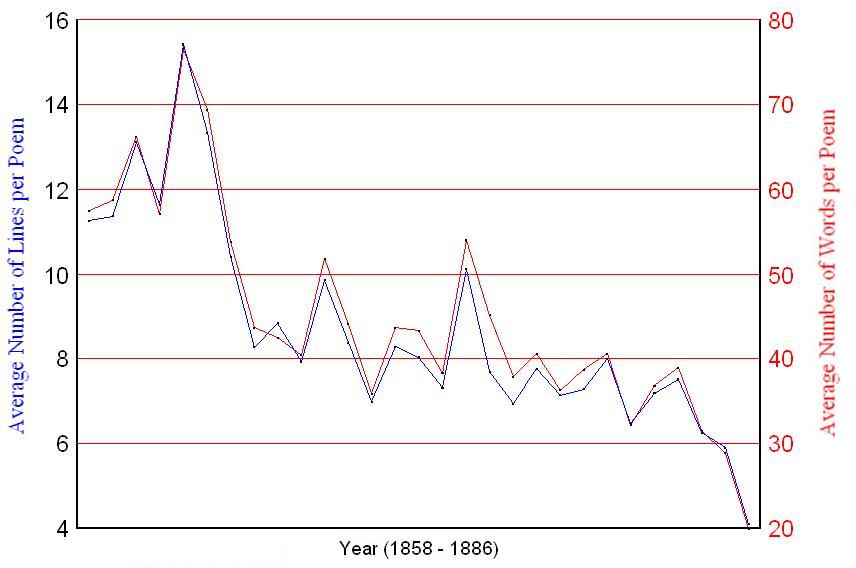

Trends of mechanical aspects of Emily Dickinson’s poetry can give a “certain Slant of light” (Fr320) to the understanding of both her poetry and her life. The trends—the frequency of the dashes, the number of words per poem, the line lengths, and the number of poems attributed to specific years—highlight interesting aspects of the life and poetry of Dickinson. Through the observation of one trend, Brita Lindberg-Seyersted, in The Voice of the Poet, has found that:

the prevailing tone of Emily Dickinson’s poetic output of the early 1860s is one of immediacy and urgency. The “spoken” character of the poems is very strongly felt. Sometimes it is a childish voice; often we hear a woman speak; at other times, we cannot identify the voice very precisely. (48)

Lindberg-Seyersted was able to establish this point of view because of a single observed trend in the poetry of Emily Dickinson, that of the connection between her increase of production and use of dashes in the early 1860s.

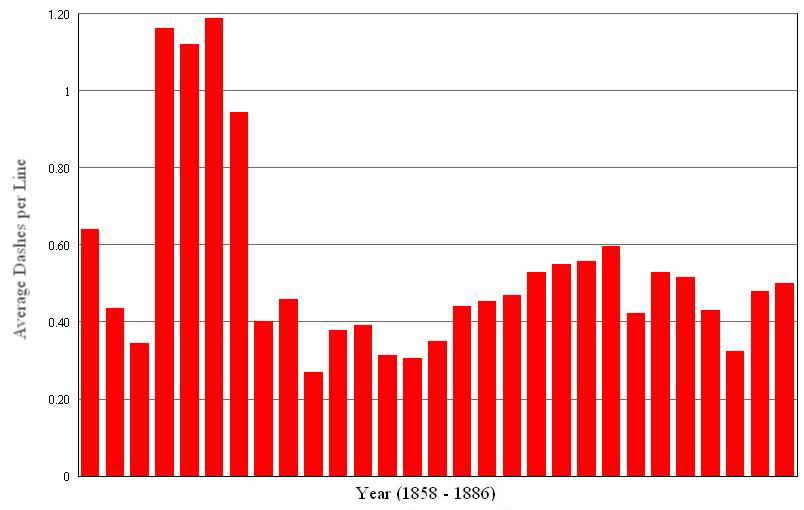

The most obvious trend in the poetry of Emily Dickinson is the frequency of dashes. It has been previously observed by scholars that an increase in the use of dashes in her most prolific period, from 1861-1865, occurred in both her letters and her poems. The following chart, one I generated for the purposes of this thesis, represents the average yearly frequencies of dash use as indicated in the Franklin texts.

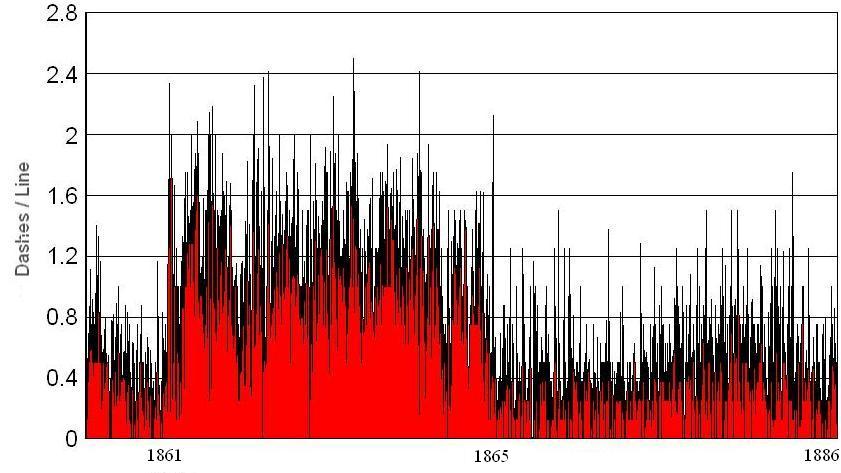

As my research shows, the average frequency of dashes in her poetry from 1861 to 1864 is generally double to triple that of the rest of her life. The connection between the years of great poetic production to increased dash use previously observed by scholars does not hold true in 1865, though. The chart begins with the year 1858, because it is the first year that scholars have attributed more than a few poems to a single year. The earliest dated poem in Emily Dickinson’s canon was placed in 1850 by both Thomas Johnson and Ralph W. Franklin. However, by this time, Emily Dickinson was already twenty years old. By the time she began writing more than a few poems a year, according to the known statistics, she was almost thirty. Looking at the frequency of dashes for each poem over the course of her poetic lifetime, we can see that the amount of poems attributed to her most “creative” years, 1861-1865, appears as a momentous writing achievement. The following graph individually represents the dash per line frequency for nearly all of the poems in Dickinson’s canon, chronologically situated from Franklin’s edition.

The same pattern occurs as the previous graph, but a greater plateau is formed because of the number of poems attributed to such a short span of time. This is why I believe that Emily Dickinson spent more time copying older poems into her fascicles than writing new poems from 1861 through 1865; the numbers are simply too astronomical.

The trend of the frequency of dashes and their correlation with poetic production does not hold up under scrutiny. First, it is hard to believe that Emily Dickinson wrote so little for the first thirty years of her life, and then in five years wrote nearly half of her canon. Afterwards, her production of poetry returns to more manageable numbers, an average of nearly twenty-seven poems per year. Interestingly, Franklin attributes 229 poems to 1865, the first year in which the frequency of dashes in Emily Dickinson’s poetry drops back down to normal. Whatever the reason for her prolific use of dashes, it diminished sometime late in 1864. So, the connection between the great frequency of dashes and Dickinson’s poetic production during these years is not entirely accurate. There is only one more year to which Franklin attributes more poems than 1865, two years earlier in 1863, and yet 1865 has one of the lower average frequencies of dash use in Dickinson’s entire life. It is obvious that Dickinson continued to copy the remaining collection of previously written poems into her fascicles during 1865, until she had finished copying all the poetry she had written before the age of thirty. It would make sense to speculate then, that whatever afflicted her from 1861 through 1864 ceased to have such a prominent effect on Emily Dickinson’s breathing in 1865, thus causing the frequency of dashes in her writing to decline.

During this time, in the transition between the years 1864 and 1865, while the letters of Emily Dickinson display similar attributes to the poems, the mood of their content shifts greatly. The use of dashes in her letters from 1861 to 1864 is elevated in the same manner as her use of dashes in her poetry. Unfortunately, there are not many surviving manuscript letters from the year 1865. Those that do exist all seem to have a lower frequency of dashes than that of the preceding four years. More importantly, the tone and subject matter of her letters also shifts greatly. In November of 1864, while in Cambridge, Dickinson mentions in a letter to her sister Lavinia: “I have been sick so long I do not know the Sun” (Letters 435). Her mood seems to shift by March of 1865, as evidenced in a letter to Louise Norcross. Dickinson is back in Amherst, before venturing to Cambridge for the last time in her life. She writes to Louise “Peace is a deep place. Some, too faint to push, are assisted by angels” and “New heart makes new health” (Letters 440).

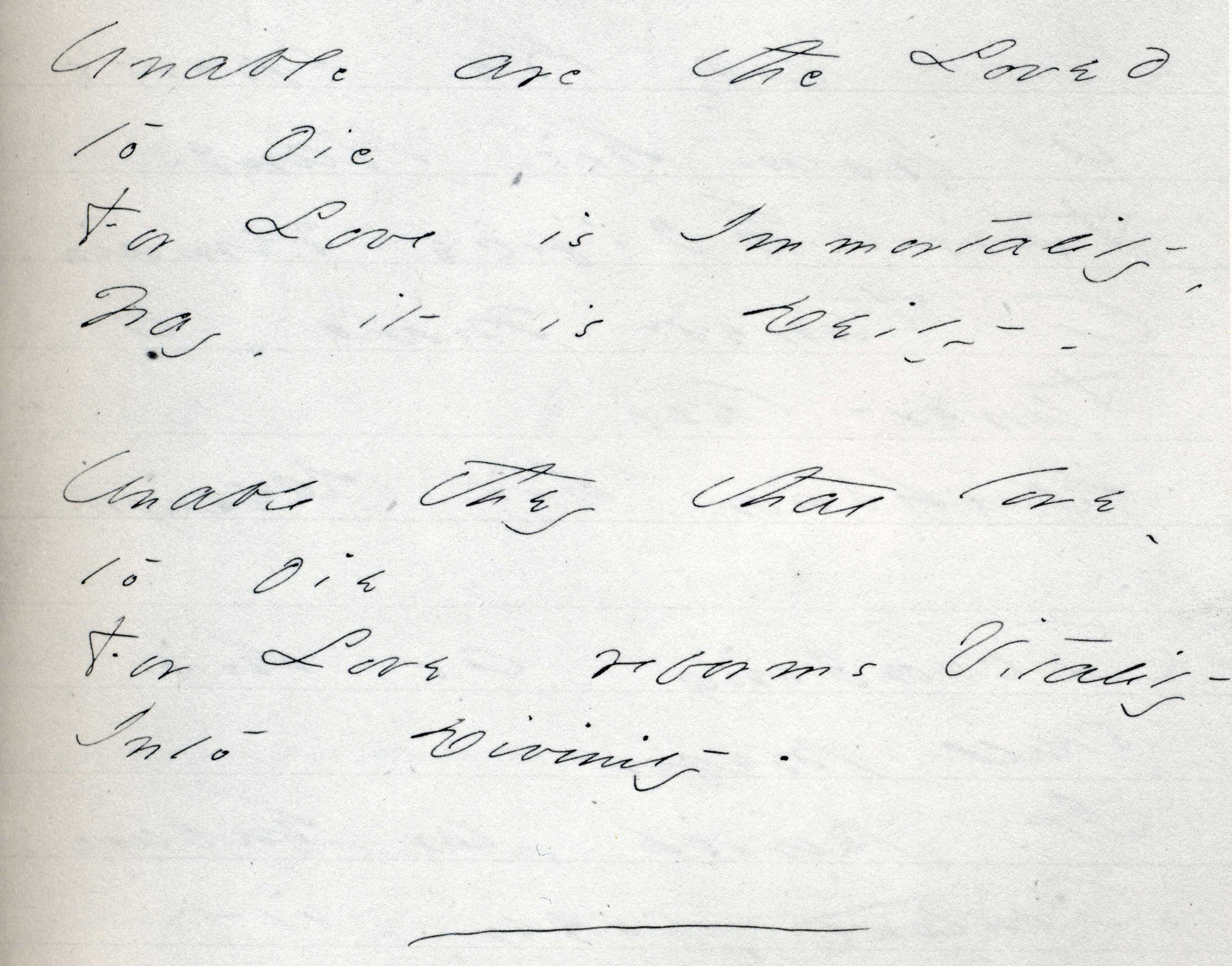

In the most telling letter during this period, a poem itself illustrates the great transition exhibiting the emergence of hope. As the frequency of dashes in her poetry falls and the quantity of poems attributed to a single year remains great, Emily Dickinson writes a letter to Susan Gilbert Dickinson upon the death of her sister Harriet Gilbert Cutler. In the letter, she writes:

Unable are the Loved – to die –

For Love is immortality –

Nay – it is Deity –

(Fr951A)

Dickinson has transitioned from the transformation of the dead from sleeping to lying in their “Alabaster Chambers” in 1861, to the inability of the Loved to die in 1865. Love is transformed from immortality to deity in this poem itself, expressing the hope Dickinson is trying to inspire in Susan Gilbert. Around this same time, according to Franklin, probably somewhat later due to the lower frequency of dashes, Emily Dickinson copies another version of this poem into her own fascicles:

Unable are the Loved to die

For Love is Immortality,

Nay, it is Deity –Unable they that love – to die

For Love reforms Vitality

Into Divinity.

(Fr951B)